New research published. There has been a lot of attention recently on the impact of climate change on the timing of nesting and the availability of prey. We have been studying Great Spotted Woodpeckers since the 1980s and have used our data on the nests and defoliating caterpillars collected over the last 20 years to examine this. Our paper has just been published in the journal Bird Study.

Does the abundance and timing of defoliating caterpillars influence the nest survival and productivity of the Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major?

A new research paper by Ken and Linda Smith

We found 836 Great Spotted Woodpecker nests between 2001 to 2016 and used the data on the clutch size, nest survival and the number of young fledged, together with data on the timing and abundance of defoliating caterpillars of oak trees to test two hypotheses.

- that breeding performance is related positively to prey abundance and

- that it is higher in years when the peak food demand of the nestlings is temporally matched with the peak availability of defoliating caterpillars.

Methods:

Our study was carried out in four mature woodlands in Hertfordshire: Wormley Wood, Hoddesdonpark Wood, Sherrardspark Wood and Hitch Wood. All the woods were dominated by oak with other species such as Hornbeam, Beech, Sweet Chestnut, Birch. and Ash present to varying degrees in each wood.

We have been studying Great Spotted Woodpeckers in these four woods since the 1980s, with attempts to find all the nests by systematic searches each year and to follow their outcomes. All the nests were in natural tree cavities normally excavated by the woodpeckers themselves. In the last two decades, we have found about 50 nests each year with nest contents determined by using high-resolution colour video nest inspection cameras on telescopic poles.

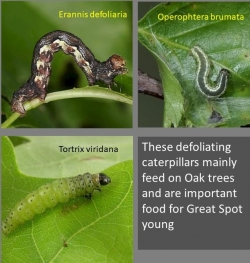

Caterpillar timing and abundance were assessed in two ways. Firstly, throughout the period from 2001 to 2016, we undertook assessments of the degree of damage to oak leaves in each wood. We had a standard procedure to score the damage on each leaf in the sample. Oak is the tree species whose leaves were most frequently consumed by defoliating caterpillars. The main defoliators in our study woods were lepidoptera larvae of Green Oak Tortrix, Winter Moth and Mottled Umber.

Caterpillar timing and abundance were assessed in two ways. Firstly, throughout the period from 2001 to 2016, we undertook assessments of the degree of damage to oak leaves in each wood. We had a standard procedure to score the damage on each leaf in the sample. Oak is the tree species whose leaves were most frequently consumed by defoliating caterpillars. The main defoliators in our study woods were lepidoptera larvae of Green Oak Tortrix, Winter Moth and Mottled Umber.

In addition to the leaf damage samples, from 2008 to 2016 we assessed the timing and abundance of the caterpillars using plastic trays set beneath oak trees to collect fallen caterpillar droppings; known as 'frass'. We operated four trays per wood, see photo, with the contents collected every 3–8 days starting from late April through to early June. The frass collected was weighed giving an indication of the abundance of caterpillars through the season. This method has been used successfully in other widescale projects in the UK.

In addition to the leaf damage samples, from 2008 to 2016 we assessed the timing and abundance of the caterpillars using plastic trays set beneath oak trees to collect fallen caterpillar droppings; known as 'frass'. We operated four trays per wood, see photo, with the contents collected every 3–8 days starting from late April through to early June. The frass collected was weighed giving an indication of the abundance of caterpillars through the season. This method has been used successfully in other widescale projects in the UK.

Results:

In total, 836 nests were found over the course of the study with 136 found during laying, 136 during incubation, 49 around hatching and 515 whilst the young were being fed.

The mean clutch size was 5.37 eggs with the mean number of young fledged considerably lower at 3.78 chicks. There were no overall differences between the woods.

The mean 'first egg' date was 26th April. There was a trend for earlier nesting over the course of the study with the first egg date advancing by 0.20 days per year. The birds were largely single brooded with only one known case of re-nesting after failure during incubation and only five other late nests indicative of re-nesting.

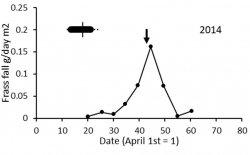

Typically, the frass started at a low level in April with the peak sometime in May and a subsequent reduction by early June. There was considerable variation in the date of the peak frass fall from year to year (median date of peak frass fall 21 May (= day 51) range 29 Apr to 7 June.

The graph shows the pattern of frass fall (in grams per square metre per day) in Sherrardspark Wood in 2014. The peak frass, indicating peak caterpillar availability, was on 15th May (= day 45). The black bar shows the range of dates when the first eggs were laid by the woodpeckers (from 13th - 24th April). The arrow shows the estimated date, 13th May, of the peak demand for food by the nestlings. You can see that in 2014 the peak food availability was closely matched to the peak food demand by the woodpeckers.

The graph shows the pattern of frass fall (in grams per square metre per day) in Sherrardspark Wood in 2014. The peak frass, indicating peak caterpillar availability, was on 15th May (= day 45). The black bar shows the range of dates when the first eggs were laid by the woodpeckers (from 13th - 24th April). The arrow shows the estimated date, 13th May, of the peak demand for food by the nestlings. You can see that in 2014 the peak food availability was closely matched to the peak food demand by the woodpeckers.

Over the years when we were running the frass trays the measured peak frass fall varied by a factor of 10 or more between woods. In 2008 the peak frass fall was about 6 g/day/m2, whereas in 2014 it was about 0.02 g/day/m2. The leaf damage index also varied considerably over the course of the study. The leaf damage index was a good surrogate measure of the caterpillar abundance with a highly significant regression between the proportion of damaged leaves and the total frass fall for the eight years for which we have data.

The caterpillar abundance rose to a peak and fell again towards the end of the 16-year study. The date of the maximum frass fall was best predicted by the mean April–May temperature. On average, the date of peak food demand of the young woodpeckers was mismatched with the peak prey by four days. The mean number of young fledged per nest was higher in years with high numbers of defoliating caterpillars and in years when the greatest food demand of the chicks coincided with the peak caterpillar abundance. Nest survival was high and was unrelated to caterpillar abundance or timing.

Conclusion:

The results show that both the caterpillar abundance and the degree of synchrony have a significant impact on the number of young produced per nest.

A high abundance of defoliating caterpillars and good synchronization of timing of breeding with the peak availability of the caterpillars can increase brood productivity of the generalist Great Spotted Woodpecker. A combination of low caterpillar abundance and a warm spring is predicted to reduce productivity considerably.

In the longer term, since the mid-1980s, the Great Spotted Woodpeckers in our study woods have advanced their first egg date by about 20 days; a rate of 0.62 days per year. Initially, this was in response to reduced nest site competition from Common Starlings but more recently in response to warmer spring temperatures with a rate of 0.40 days per year from 1990 onwards. Between 2001 and 2016 the mean first egg date advanced by only 0.20 days per year – a figure similar to that reported for other species in the UK. In spite of these big changes over the last 30 years the birds have maintained synchrony with their prey except in the warmest springs.

Full details of the study, results and statistical analysis are published in our paper in the BTO journal Bird Study

Full details of the study, results and statistical analysis are published in our paper in the BTO journal Bird Study

Ken W. Smith & Linda Smith (2019):

'Does the abundance and timing of defoliating caterpillars influence the nest survival and productivity of the Great Spotted Woodpecker Dendrocopos major? '

The paper is available online on Taylor & Frances website at the link: https://doi.org/10.1080/00063657.2019.1637396

Downloads are free to subscribers and for a charge otherwise.

If you do not subscribe to Bird Study and would like a pdf copy of the paper